How does the food get there? How is it prepared? Do they just stick in a microwave oven? Is that real white meat, like McDonalds’ claims?

For better or for worse, airline food is a mystery. Because, most of the time, it’s not like there’s much choice in the matter. It turns out being in the air does all sorts of weird things to food and human perception.

Fun fact: It would seem that the palate changes considerably up in the air, and to get the same oomph on the ground, chefs must often double down on both the flavor, umami, and acidity to resemble a dish created a little bit closer to home.

So, perhaps, there is an actual legitimate reason why food may seem worse 30,000 feet up in the air, or at least, have that reputation.

To get an idea of what happens, Singapore Airlines was gracious enough to let us get a sneak peak of exactly what goes on. It’s a true process that has even led the airline to create a super-duper pressurized kitchen that replicates the exact same environmental cabin conditions at its home base in Singapore.

Short of flying there, we opted to go behind the scenes with the airline at John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK) instead.

So while the plane is sitting on the ground..

In general, airline food is never cooked onboard, simply because most planes don’t have the equipment. It would also create a logistical nightmare for the flight crew, many of who are meeting each other for the first time ever.

Instead, the food is often prepared down on the ground, at each individual airport. Many often airlines choose to use a catering group, or whatever in-house kitchens they choose to use at each individual airport. The quality of the food really depends on who’s cooking at the departure location.

Every time the plane touches down for an international flight, all the food onboard is immediately destroyed in an oven according to customs regulations, burning everything down to a crisp at a temperature up to 700 degrees Fahrenheit. Meanwhile, all the silverware is cleaned in a washed in a commercially-sized industrial dishwasher.

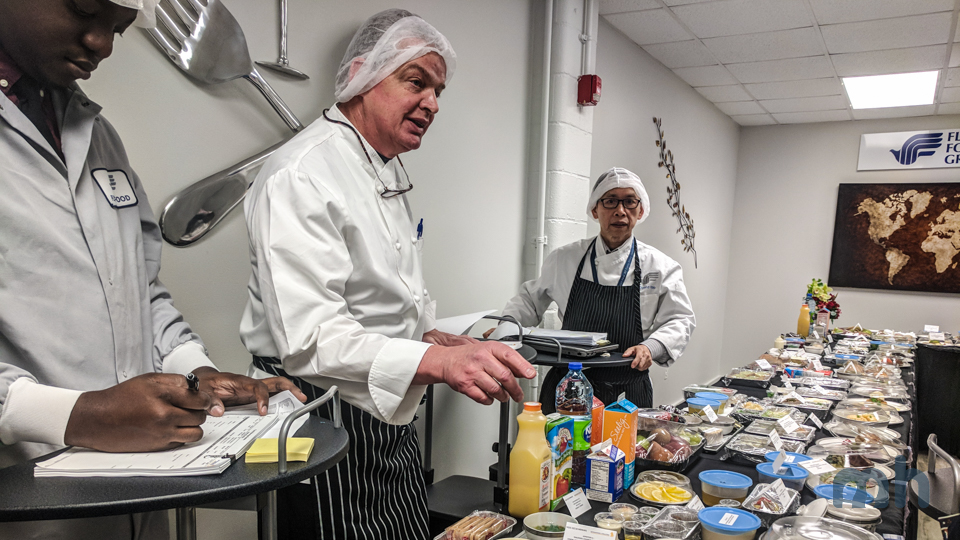

Then the kitchen loads everything onboard the aircraft. In this case, Singapore is served by Flying Food Group out of JFK. Bob Son, a vice president at the company, mentions, “The plane is cleaned, and then when the plane is ready to go, we load everything from water to food, you name it, and the plane becomes full again, in every city.”

(Flying Food Group services 70 airlines in total across the board, but services 24 airlines at JFK specifically. Only 2 airlines, JetBlue and Hawaiian, are domestic, because, well, domestic airlines don’t really serve food. Load up on peanuts, folks.)

No, the same food is not served on every airline. Each airline has its own dishes, preferences and tastes. More or less, Son notes, “it’s like having 70 different children.”

Food actually tastes different up in the air.

The phrase 'cooking is a science' has never rung more true, especially when speaking about airline food. Everything from the humidity of the cabin and the altitude can literally alter what you taste onboard, meaning things have to be prepared completely differently on the ground.

Flying Food Group does the best that they can to replicate plane conditions on the ground, by first precooking the food, and then reheating it. It is at that point, Leanne Koh, Singapore’s JFK station manager, is in charge of checking the food every quarter, to make sure all the offerings hold up to snuff (or taste).

Koh mentions, that in particular, stews and curries do very well for Singapore’s flight out of JFK through Frankfurt, and are a particular passenger favorite. But there is more to it than what the passengers like.

“I [think about things like], is the rice in proportion to the meal, is the sauce flavorful enough because it’s not just about the salt, right? It’s about the flavor, and your taste buds with the altitude is not as sensitive when its 30,000 feet up in the air, so you have to amp up the flavor.”

The same thing also applies to acidic dishes, which are affected by the altitude. Vinaigrettes can be tricky to pull off if not done correctly, and will often require an extra squeeze of lemon (or two, or three) to get a dish where it needs to be.

Koh’s job, essentially, is to check and taste the food to make sure it is up to standard, working closely with the chef and kitchen on each dish on presentation, taste, and quality control. To replicate the experience, the food is often prepared and then reheated the exact same way to make sure the food tastes exactly like how a passenger would experience it.

Loading up all that food... and silverware

There’s a lot of logistics that go down to how much food and silverware is carried onboard, simply because an airline’s biggest expense is fuel. This is no exception with Singapore Airlines.

Because the silverware is reused between flights, it is also important that there is menu consistency between its previous and next route—but not too much, lest the first- and business-class passengers, who tend to be the most frequent flyers, notice.

The airline must maintain a fine line between balancing the cargo weight of the silverware and making sure the menu isn't monotonous. No two lobster rolls in a row for you!

Truly, the real role of the flight attendant is making sure all the passengers onboard are safe. But, in order to make it easier for the cabin crew to reheat and plate the food, the meal is often portioned out in on individual trays, then photographed, which is then given as a plating guide to the flight attendant. (In some cases, circular dishes may be pre-plated with a shirt collar.)

(For the record, the silverware used does dictate the class of service.)

Cooking airline food isn't exactly what you think it would be like.

Even bread just isn’t bread up in the air. Everything is prepared on the ground, except for eggs.

Singapore Airlines has a proprietary, secret way of cooking scrambled eggs onboard. Like, for realsies. (They didn’t tell us.)

In general, the food is cooked about 40% of the way through on the ground, and then placed in a blast chiller to prevent the residual heat from continuing to cook the piece. It stays there, which is maintained at a temperature around 39 degrees Fahrenheit, just slightly above freezing point.

Later, the food will later be reheated on the aircraft either using a convection oven, or steamer, depending on the actual item.

There are some interesting nuances, since cabin crew don’t often have access to the tools they would have on the ground. Garlic bread is one such interesting item, since the garlic needs to be sautéed on ground first, and then processed into a compound butter beforehand. There is simply no way to toast fresh, raw garlic onboard, and even if it was possible, just about everyone would hate you.

Breads also pose a unique problem because of the plane cabin’s humidity, which typically hovers around 15%.1 Since breads can dry out quickly, this means a couple of things. Breads served onboard typically need to have a crust, be sliced, and already toasted. Pretzel bread and challahs don’t do well in the air and are much less likely to make it into the normal selection.

This also affects rice dishes, which need to be layered with a thin slice of cabbage to keep the grains fresh and moist.

James Boyd, a spokesman for the airline, also pointed out that the meat cuts often tend to be compact and thick for a reason, allowing them to be served (properly) medium rare. “What this allows us to do, is that when we reheat, we can reheat it so that the inside stays rare, and maintain the structure of the cut.”

Plus, I assume, there’s all that convection oven crust browning action going on there. (The steamer is for, um, creating moisture.)

In general, the list of meats that tend to do well up in the air might surprise the average cook: chicken (no surprise there), salmon, cod, sea bass, beef, prawns, and scallops all tend to reheat well. Seafood, in other words, one of the easiest things to overcook, thrive in the steamer. Smoked salmon is another favorite.

But duck and turkey? Probably not. It doesn’t mean the airline isn’t striving to push the envelope, notably exploring with several sous vide offerings, and a collaboration with Michelin chef Alfred Portale, who heads up New York’s Gotham Bar and Grill. (In Los Angeles, the airline works with noted chef Suzanne Goin.)

But, expectations are generally high for those twelve people in the famed Singapore suites, the 86 people in business, and anyone else who might have selected the book-to-cook option in premium economy. I’ll still be sitting back in economy with my Häagen-Dazs, though.